|

Name: BarryNet Articles and Reviews Date/Time: 3/2/2021 10:14 PM Subject: 'When October Goes' – Music by Barry Manilow, lyrics by Johnny Mercer

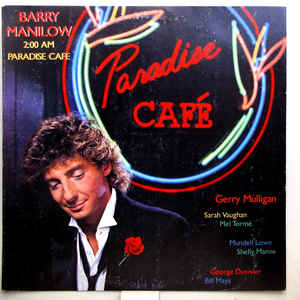

Bistro Awards, 01 March 2021 The lucky thirteenth installment of Cabaret Setlist centers on “When October Goes,” a short, bittersweet, and evocative ballad of love and loss. The song, which debuted in 1984, has gradually come into its own as a modern standard. It has a most unusual pedigree. Its words were written by one of the most beloved lyricists of the mid–20th century: Johnny Mercer. Its melody was composed by pop vocalist Barry Manilow about eight years after Mercer’s death. The singing star had spent the earliest years of his career in New York City cabaret venues, most famously as pianist for rising star Bette Midler. Manilow first performed “When October Goes” on his album 2:00 AM Paradise Café, a suite of original, jazz-inflected melodies that featured guest performances by Sarah Vaughan and Mel Tormé. Here’s the abridged story of how Manilow came to set Mercer’s lyric for the song: A few years after the lyricist’s death, his widow, Ginger Mercer, arranged to send some unfinished lyrics to Manilow. Toward the end of his life, her husband had become fond of the younger man’s music. She wondered—would he want to try his hand at setting some of Johnny’s unfinished pieces? Manilow was game, and he soon set “When October Goes.” The number became the centerpiece of the Paradise Café album, which climbed to #28 on the Billboard 200 chart and eventually went Platinum. Much of the song’s appeal resides in its simplicity. “When October Goes” has no introductory verse. The main melody centers around a series of phrases of six syllables that gently rise and then softly fall, as if they are reaching for something that’s not quite accessible. On the fourth phrase, the notes end in an ascension rather than a drop, creating a hint of hope, perhaps. The melodic line takes different turns as the tune progresses, but the song has no bridge to speak of. The melody seems to come to an end. But then a coda is heard, providing a release and a strange kind of benediction, a mere three lines long. As for the lyrical content, it is similarly uncomplicated. At the top of the song, the protagonist, communicating in present tense, is focused on the surrounding autumnal landscape, both natural and human-made: the year’s first snowflakes, chimneys with smoke curling from them. The most striking thing to me about the lyric is that it begins with a conjunction: “And...” This suggests that the protagonist is in the middle of a thought or a conversation or a daydream before the first note is sung. “And when October goes / The snow begins to fly.” The question of what may have immediately preceded that thought gives the song a hint of mystery, right from the beginning. The character’s attention soon moves upward from smoky roofs to distant airplanes passing overhead. Then, immediately, the focus shifts back to earth, to a group of children scurrying home as night falls. Their joyful enthusiasm for life inspires memories of the protagonist’s own past: “Oh, for the fun of them, / When I was one of them.” The character’s nostalgia finally touches on a dream of embracing a loved one. This is the one point in the song when the listener is addressed as “you”: “...You are in my arms / To share the happy years.” This “you” is likely a romantic partner, but there is nothing in the song suggesting it couldn’t be a parent, a child, or a dear friend. The protagonist fights back tears before the coda, in which a kind of truce is reached with both the coming winter and the human loss that winter signifies. It wasn’t long after the success of Paradise Café that “When October Goes" prompted some notable covers ... Rosemary Clooney’s 1987 take is steady and straightforward. She sings the number without vocal frills. Clooney’s protagonist pours out her heart—broken though it may be—without flinching. In this live performance, there’s often a slight smile, both on her face and in her voice ... By 1991, Manilow had set several other lyrics from among those sent to him by Ginger Mercer. They were showcased in Nancy Wilson’s album With My Lover Beside Me, which Manilow produced. "When October Goes" is a highlight of the collection ... The robust baritone of the late Robert Goulet makes for another very pleasing rendition. Goulet’s powerful singing is accompanied by an almost samba-ish soft-rock styling that flares into something more flamboyant at key moments ... A 2003 recording by jazz performer Diane Schuur employs a lavish orchestration to underscore the vocalist’s avid throb. Schuur, near the end of the cut, includes the sort of vocal embellishments that the serene Clooney avoids, but her version is equally earnest and strong ... “When October Goes” [has been paired] or blended with it is “Autumn Leaves,” which also happens to have a Mercer lyric. [The] late Nancy LaMott was one of the first singers to put the two songs together (in 1992). Listening to her version (with an arrangement by Christopher Marlowe), you’ll understand the impulse for pairing the numbers ... Chicago-based vocalist Megon McDonough sang "When October Goes" as the title track of a 1991 album, When October Goes - Autumn Love Songs, which included tracks by various performers. [McDonough] has long been a Manilow fan, but she came to know this song through the Clooney version ... Bistro Award recipient Lisa Viggiano performed the song in 2002, when she was living in the San Francisco Bay area, at a gala show for the Richmond/Ermet Aid Foundation, which provides funding for AIDS organizations, homeless youth, and anti-hunger programs ... The version that two-time Bistro Awards honoree Amy Beth Williams created for a 2015 Don’t Tell Mama show, Crazy to Love You, is considerably more complex than some of the previously mentioned renditions. [Williams] was a fan of Manilow’s. [She] had latched onto “When October Goes” during “an incredibly intense relationship change.” I’m about to wrap up my examination of “When October Goes” when I receive a response to an email I’ve sent earlier. Barry Manilow has agreed to speak with me about his song. To say that this news makes my day is an understatement. Early on a February afternoon, I receive the phone call from Palm Springs. After explaining exactly what I want to talk about, I ask Manilow about having received those lyrics from Ginger Mercer more than 35 years ago. “It’s a very short story...” he says. “Back in the early eighties, I guess, I got a phone call from my record company. This was after Johnny Mercer had passed away. Ginger Mercer -- his widow -- had discovered a stack of lyrics that he had written—that nobody had ever put music to. They weren’t all completed, and some of them were in his handwriting and some were typewritten. She didn’t know what to do with them, and she liked my work and asked my record company whether they could get [them] to me.” Manilow told the record company to send the lyrics his way. He still has them, along with the manila envelope in which they had arrived. He recalls first looking over the lyrics in that packet: “Some of them sounded like they should have been in Broadway musicals... They looked like they were coming from a [theatrical] situation. They were ‘cowboy’ kind of lyrics, and I don’t know what situations they were in, but they weren’t all pop songs. But some of them were. They were lyrics that sounded like a Johnny Mercer pop song that any one of those great composers would have put melodies to. And one of them was ‘When October Goes.’ That was the first one that I pulled out. And I stuck it on the piano, and I hit the cassette machine. I hit the piano keys and I read the lyric and I sang the song. I shut the cassette machine off, and that was it. I never went back. I never had to fix it up. I never had to change anything. It was just right there. It was written before I got there. I don’t know how something like that happens. Maybe Johnny was sitting on my shoulder and showing me what he wanted.” Whether or not something paranormal had occurred, Manilow was happy with his composition. He added “When October Goes” to the stack of songs he planned to use on his upcoming album. “When we recorded it, the band knew that there was something going on with that song. I had a second pianist there. I played piano, but I had a real jazz pianist, Bill Mays. And he looked up and he said, ‘Whoa, this is big.’ And it went on the album, and it was always the standout cut from the Paradise Café album.” Manilow describes that final recording in detail in his liner notes for 2:00 AM Paradise Café. [The] events of that date were, in their own way, as serendipitous as his randomly picking up the “When October Goes” lyric from that stack of papers in Ginger Mercer’s manila envelope. He had taped the songs, along with their musical connective tissue, during the last couple of studio dates, but at the very end of the final session, he decided to try recording the entire album in a single take. “They started to roll the tape - it was tape at the time. We started at the beginning and we ended at the end. And that’s the album. It was just one long take. We had rehearsed for a week, and [the musicians] knew these songs in their bones. It was just thrilling.” He claims that the Paradise Café album changed his musical life: “That was the moment I said, “OK, this is why I’m in the music business. And I can’t go back to doing ‘I Write the Songs.’ I can’t do it anymore. And then I left Arista Records and Clive [Davis]—with his brilliant singles and charts and bullets and all that stuff I’d been doing for 10 years. That changed everything.” Of course, Manilow didn’t abandon his pop career altogether. Certainly, he has continued to sing “I Write the Songs” over the decades. But he’d come to the awareness that there were other musical options to be considered. Of the 35 or 40 Mercer lyrics that Manilow received, he has found melodies for about 15. Inspiration didn’t come quite as readily to him for these other numbers as it did for “When October Goes.” In addition to composing music for songs on the Nancy Wilson album, Manilow set a Christmas lyric of Mercer’s, “I Guess There Ain’t No Santa Claus.” He included that jocular song, about being lovelorn during the Christmas season, on his first holiday album. Generally, he believes that the melodies that come quickly to him tend to be more successful. “I think the listener can hear the struggle. I find that when I don’t have to struggle, then I know I’ve got something... ‘Copacabana’ was the same thing. Bruce [Sussman] and Jack [Feldman] gave me the lyric, and I just played it down, and that was it.’” In 2000, Manilow made a couple of New York City appearances that commemorated his connection with the cabaret community. He showed up at the annual Cabaret Convention, produced by the Mabel Mercer Foundation, on an evening when the artistry of a Mercer named Johnny was celebrated. And he appeared at the Manhattan Association of Cabaret Awards, where he was presented with that year’s Board of Directors Award. “That was great...” he says, “Those people with their stories and their medleys and their humor and their passion, I took everything I learned from them and put it into the pop world. And I think that really made a difference with my career. ’Cause nobody was doing that. There were no guys that were doing that. Everybody was either rock and roll or just jumpin’ around the stage. I was doing what [cabaret performers] were doing: talking to the audience, kibitzing with them, doing medleys... These people were filled with ideas, and I just loved working with them. And it was an honor to get an award from them and to see them all, from Jamie deRoy to Jane Scheckter. I’d played for all of them, and they were my friends.” When I let him know that “When October Goes” remains popular in the cabaret community, he is pleased. “It makes me feel great that those people that I admired so much discovered a song that I wrote.” I ask him if he has any advice for singers thinking about performing the number. “Warm up - there’s a high note at the end,” he jokes. But then he adds: “Just tell the truth. Don’t worry about the notes, just tell the truth. And it’ll work.”

|

![]()